Marozi

Marozi: How the Lion Got His Spots

By Craig Heinselman

"Then the Ethiopian put his five fingers close together (there was plenty of black left on his new skin still) and pressed them all over the Leopard, and wherever the five fingers touched they left five little black marks, all close together. You can see them on any Leopard's skin you like, Best Beloved. Sometimes the fingers slipped and the marks got a little blurred; but if you look closely at any Leopard now you will see that there are always five spots -- off five fat black finger-tips." From Rudyard Kipling's "How the Leopard Got His Spots"

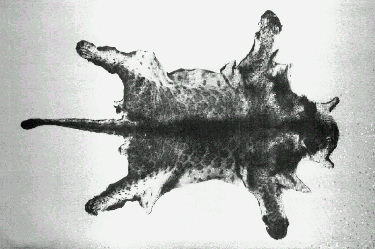

A Drawing of the Marozi (spotted lion), courtesy of William M. Rebsamen

Onza, King Cheetah, Eastern Panther, Thylacoleo carnifex, these are all names of enigmatic felines (or feline like animals) from across the globe. They are not alone, the list is staggering of mysterious cats, but amongst them are a few rare examples where physical proof possibly exists that adds credence to local legends and travelers tails. The marozi is one such rare example, the Spotted Lion of Africa.

The marozi is little remembered today, and sadly may no longer even exist as the reports have for the most part stopped during the last 40 years. The brunt of the evidence for the once existence of this lion starts in 1931. In that year a farmer in the Aberdare Mountain area of Kenya shot two small lions at an elevation of around 10,000 feet. These specimens where eventually mounted as trophies, and caught the attention of the Game Department. Upon further examination by officials at the Game Department in Nairobi the skins became a conundrum. As the skins where from a male and a female of pubescent age, but the skins where spotted something that only appears in lions at an early age. With those two skins, the chronicle of the marozi begins.

Kenneth Gandar Dower steps into the picture. A well-to-do adventurer he wished to see Africa's wildlife with his own eyes:

"Mine was not a promising situation when I found myself stranded in Nairobi. My only assets were a love of Rider Haggard and a vague half-knowledge of what I wished to do. I wanted to see big game in their natural surroundings, to take their photographs, and, once that was done, to fit myself to go alone into the great forests. I wanted to discover and to explore. Yet I could not speak Swahili. I had no fiends in Kenya. I had scarcely taken a still photograph (that had come out) or fired a rifle (except upon a range). My riding was limited to ten lessons, taken seventeen years previously when I was nine, on a horse which would barely canter. My shy suggestions of the possibilities of new animals brought only rather scornful jokes about the Naivasha Sea Serpent and the Nandi Bear." 1

And so at the age of 26 Kenneth Dower sets forth. Not immediately to find a mystery animal, but a animals and nature in general. He hooks up with a farmer / guide / hunter named Raymond Hook, who becomes vital in the eventual search for the spotted lion. Much of Dower's expeditions are written about in his 1937 The Spotted Lion, although the title itself is misleading. He touches on during his exploration and expeditions such items as the Nandi Bear, discovered species, black lynxes as well as the marozi. Three months after arriving in Africa Dower set off in search of the legendary animal he had heard of, and that his now friend Raymond Hook had said was "Rubbish". But, the questions remain as to where to search, what to search for and what to do if one is ever found:

"This opportunity, given so undeservedly to a novice, who three months ago had never been to Africa or really ridden a horse or fired a rifle at a living thing, was almost too great a responsibility to bear. I felt small. Even with Raymond's help, how could I hope to find this rare animal, the very existence of which had for so long been unsuspected, in 2000 square miles of wilderness, through which we could hardly travel, to find it and track it down, and shoot it, or photograph it and capture it alive?" 1

A burden of proof to be found. The evidence collected during this expedition was circumstantial, a spoor found along side a series of tracks taken to be that of a marozi. For the series of tracks from two animals was taken to be a male and a female. The smaller set of tracks to be female, the larger ones male. The larger track being bigger than a leopards, but smaller than a lions. As the animals where following a trail of buffalo it is assumed that they where hunting, and hence not cubs, but rather a hunting pair of lions. And again at a latter time at an elevation of 12,500 feet a track from a lion was found, again taken to be from the spotted variety due to the location. And at an even latter date the part missed the possibility of seeing one of these animals by a matter of a single day.

The expedition had failed in finding conclusive proof of the marozi, but the effect of the search did not fail. Dower is the single person to push the marozi to the attention of the world through the publication of articles in The Field and through his book, as well as the collection of anecdotal accountings from the natives. In these accountings there is a distinct separation among the people of the area, without having seen the specimen's skin that Trent had shot, of the normal lion and the spotted lion, simba and marozi.

From his writings Dower's spotted lion became well known and for years after the first article in 1935 sporadic accounts where published in The Field. With the last in 1948 by a J.R.T. Pollard, also a friend of Raymond Hook. In this letter Pollard emphasizes that Hook believed the possibility was there that could be a spotted variety of lion, but that the evidence was not sufficient to prove it. Which is similar to what Dower had written about 11 years prior in which he quotes Hook as saying the marozi stories where "Rubbish".

Yet, some of the other reports from The Field are as interesting. For instance also in 1948 an entry by G. Hamilton - Snowball recalls learning of the marozi prior to Dower's expedition. He even may have spotted a pair of these animals at an elevation of 11,500 feet along the Kinangop Plateau. These animals retreated prior to his being able to shoot one, but the natives with him where heard to be whispering the word marozi amongst themselves at the sight of these animals.

Still more reports where around prior to the first article by Dower. Colonel Richard Meinertzhagan had reportedly heard the name marozi prior to 1908. And Captain R.E. Dent, a game warden, reportedly spotted four of these animals at an elevation around 10,000 feet in 1931. And a specimen may have been killed in a trap during this time as well. Undeniably something was being seen in the Aberdare Mountains earlier this century. The question remains what was it that was being seen?

Theories as the origin have been mixed. The main ones have been that the marozi is a natural crossbreed of a leopard and a lion, that the animals seen where abhorrent specimens of lion, that the natives made up the stories to please the explorers, and that the animals seen are spotted due to tricks of light. It is possible that some of the explanations can account for some of the sightings and reports, but it is doubtful that they can explain all sightings away.

If these animals where deliberate hoaxes by the natives, then why would they whisper among themselves, probably unaware they where being overheard, that the animals seen where marozi. The classic example of this would be the report by G. Hamilton-Snowball, wherein the natives whispered the name while he was trying to get his rifle to shoot one. There was a single expedition, split into several smaller ones but encompassing one large expedition only, run by Kenneth Dower. In essence there was no financial gain to be made by creating this legendary animal, as no future expeditions ever searched for the animal.

Biologically speaking the hybrid theory also is flawed. Although crossbreeds to occur, they are in captivity and the offspring are traditionally sterile. In the wild a crossbreeding between species would be especially rare and unlikely, although genetically possible. The fact remains that species are isolated, and remain so due to behavioral differences and varied geographies that act as barriers to inhibit crossbreeding.

There are cases of leopons (lion and leopard mix) and other feline mixes, like ligers (lion and tiger mix). And these leopons do express the characteristics of the marozi, especially the intermediate size and spotting. But, thus far this phenomenon has only occurred in controlled environments and not in the wild. To have a population of leopons in the wild would require successful natural crossbreeding and then fertile offspring that mate and produce other fertile offspring. Each becomes statistically narrower in possibility as the reproductive cycle continues, in this case at least 40 years worth of reports and thus more than one generation of animals.

The other possibility, aside from a separate species of lion, is that of abhorrent specimens of lion. This is not a new occurrence, and has taken place with the birth of white lions from normal lions. The first authenticated reports of the white lions come from Timbavati Nature Reserve (near Kruger National Park). Where in 1975 2 the mating of normal lions was recorded, and the birth of two white lions documented (named Temba and Tombi). These where not albino specimens, rather white lions with lighter eyes, but otherwise normal animals. Other incidents of abhorrent specimens of felines are documented such as the white tiger and even the king cheetah. So, the possibility of this being an explanation for the marozi is there and with the proper mixing of dormant genes and some inbreeding then an explanation could arise, however, the geographic distribution of the traditional lion does not foster this scenario. As these marozis are reported from high wooded country, and not the plains.

One is then left with the unknown question of what is the marozi? If the anecdotal reports stood alone then the animal may be viewed as a curious account in natural history, however that is not the case here. The skin of one of Michael Trent's lions shot in 1931 still exists along with a possible skull at the Natural History Museum in London.

Few possible specimens of mystery animals exist. And some, as in the case of the possible onza specimen killed in 1986 in Sierra Madre, Mexico, turn out to be of a known species that may be an adaptive specimen to a particular environment 3 . The Trent skin however, may be something altogether different and establish that there may have once existed a species of lion that exhibited a spotted coat. However, little examination of this skin and the possible skull from Trent has occurred.

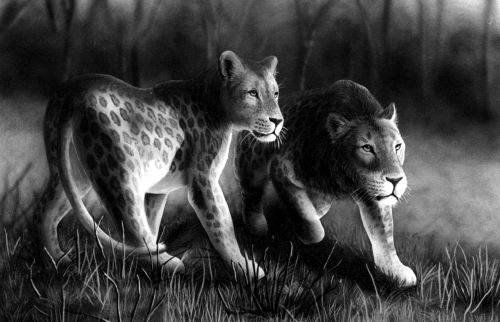

A Marozi Skin. This is 1 of the 2 specimens killed by Michael Trent in 1931.

From the book "The Spotted Lion", 1937, by Kenneth Gandar Dower.

R.I. Pocock of the Natural History Museum in London examined the specimens prior to 1937. His is apparently the last full examination of these specimens. His findings are as follows:

"It is a male, measuring approximately: - head and body 5ft. 10½ in., tail, without terminal hairs of the tuft, 2 ft. 9 in., making a total of about 8 ft. 8 in. This is of course small for adult East African lions, of which the dressed skins may surpass 10 ft. over all. From its size I guessed it to be about three years old, a year or more short of full size. There is nothing particularly noticeable in its mane, which is small and, except on the cheeks, consists of a mixture of tawny, grey and black hairs, the longest up to about 5 in. in length. … the peculiarity of the skin lies in the distinctness of the pattern of spots, consisting of large "jaguarine" rosettes arranged in obliquely vertical lines and extending over the flanks, shoulders and thighs up to the darker spinal area where they disappear. They are irregular in size and shape, the largest measuring 85 by 45 or 65 by 65 mm. In diameter. Their general hue is pale greyish-brown, with slightly darkened centres, but at the periphery they are thrown into relief by the paler tint of the spaces between them. On the pale cream-buff belly, the solid richer buff spots stand out tolerably clearly. The legs are covered with solid spots, more distinct than the rosettes of the flanks, and on the hind legs they are more scattered and a deeper, more smoky grey tint than on the fore legs. The skulls of the pair of spotted lions secured by Mr. Trent were not preserved when the animals were skinned; but a skull presumed to belong to one of them, with all the teeth and the lower jaw missing, was subsequently picked up near the spot and submitted to me with the skin. It is a young skull with all the sutures open, showing it had not attained full size and may well be the estimated age of the skin. It is not sufficiently developed to be sexed with certainty … The skull in question may prove to be that of a slightly dwarfed lion with the teeth and skull reduced to about the size of those of an ordinary lioness." 1

According to Daphne Hills of the Natural History Museum in London others have evaluated the specimens over the years, but that there is little to add to Pocock's evaluation. However, there may still be a glimmer of possibility in that Hills has also stated:

"It is probable that the specimen will be included in any future DNA studies…".4

Whether these studies are ever conducted remains to be seen, but the specimens are still present in 1999 in the museum collection.

What is known thus is that the Aberdare's spotted lion is a small lion intermediate in size between a plains lion and a leopard. They travel in groupings of two and in at least one incident four where seen together. They exhibit a striking spotted appearance into adult hood. The males lack a traditional mane, and if present it is minimal at most. The geographic distribution in the Aberdares is in the higher elevations of the mountains within the treelines. The natives also firmly establish that there is a difference between the two lions, hence two different names simba and marozi.

The enigma of the spotted lion has not been answered, the more one looks the more questions arise. However, the one fact that stands out is the 1940's there have been no reports from the Aberdare Mountain area. A disturbing fact that may answer the enigma once and for all, the spotted lion is gone now, at least in that area. But, other locations in Africa have similar reports of smallish lions with spotted coats. So hope may still remain that the ikimizi from Rwanda, abasambo in Ethiopia, kitalargo in Uganda, and so forth. 4

These scattered reports from the continent also may add fire to the debate that the marozi was a crossbreed or an abhorrent representative. As, if one population exists then the possibility of an biological mixing is possible (although unlikely), however if scattered reports separated by hundreds or thousands of miles report a similar animal, then there may well be a distinct mountain species of lion still existing. Perhaps one day another intrepid explorer, like Kenneth Gandar Dower, may stumble upon a pocket of spotted lion reports and once and for all squash the question of their reality into the current times.

Selected Sources:

Alberton, David, Wild Cats of the World, Blandford, London (UK), 1998

Bille, Matthew A., Rumores of Existence, Hancock House, Surry (BC, Canada), 1995

Bottriel, Lena Godsall, King Cheetah, E.J. Brill, Leiden (Netherlands), 1987

Carmony, Neil B., Onza! The Hunt for a Legendary Cat, High-Lonesome Books, Silver City (NM, USA), 1995

Dower, Kenneth Gandar, The Spotted Lion, Little, Brown and Company, Boston (MA, USA), 1937 1

Downes, Jonathan , Between the Lions, Animals & Men Issue 12

Dratch, Peter, Roslund, Wendy, Martenson, Janice, Culver, Melanie, O'Brien, Stephen, Molecular Genetic Identification of a Mexican Onza Specimen as a Puma (Puma concolor), Cryptozoology, Volume 12, 1993-1996 3

Heuvelmans, Bernard, On the Track of Unknown Animals 3rd Edition, Kegan Paul International, London (UK), 1995

Hills, Daphne, Personal Communication January 13, 1999 4

Kipling, Rudyard, Just So Stories, Lancer Books Edition, New York (NY, USA), 1968 (originally published 1902)

Marshall, Robert E., The Onza, Exposition Press, New York (NY, USA), 1961

McBride, Chris, The White Lions of Timbavati, Paddington Press, Ltd., New York (NY, USA), 1977 2

Naish, Darren , Lost Lion Renaissance, Animals & Men Issue 12

Nowak, Ronald M., Walker's Mammals of the World 5th Edition Volume I and II, The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore (Maryland, USA), 1991

Patterson, Lieutenant-Colonel J.H., The Man-Eating Lions of Tsavo, The Field Museum Zoological Leaflets No. 7, , 1926

Schaller, George B., The Serengeti Lion, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (IL, USA), 1976

Shuker, Karl P.N., Mystery Cats of the World, Robert Hale, London (UK), 1989 5

Shuker, Karl P.N., African Mystery Cats, Cat World, No. 213, November 1995

Shuker, Karl P.N., Lion Spotting, All About Cats, November/December 1998

Turner, Alan, The Big Cats and Their Fossil Relatives, Columbia University Press, New York (NY, USA), 1997